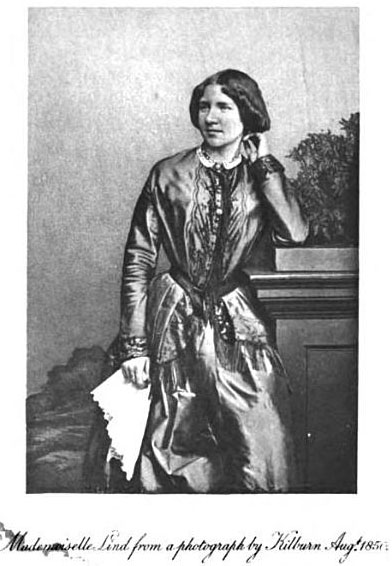

In daguerreotypes, Jenny Lind today strikes

us as unexceptional: modestly plain (if not homely), with a serene, even

reserved countenance. This unassuming Swedish woman was an international opera sensation in the nineteenth century. Our inability to hear her voice or

witness her dramatic power may explain why her fame has faded away.

Biographers who wrote tributes to the opera singer during her career

describe her performances with manifest emotion, giving us an indication of

her captivating presence on the stage. Known as the “Swedish Nightingale,” she began in

lower-class obscurity and rose to become recognized by royalty as an

indigenous treasure. On concert tours, overwhelming crowds thronged to greet

her arrival; and, after a show in London, even Queen Victoria threw a bouquet down to

her from the royal theater-box (Rosen). She remained humble in the midst of

celebrity and is esteemed alongside great women of prosopography for her

vocal talents as well as her charitable example—after retiring professionally, she gave free

concerts to raise donations for hospitals and the needy. Rediscovering her

through written accounts, along with a wealth of popular-culture materials,

including ephemera, cartoons and advertising campaigns, creates a picture of

an exceptional figure whose biography intersects with issues of class, the

arts in society, and public women.

In daguerreotypes, Jenny Lind today strikes

us as unexceptional: modestly plain (if not homely), with a serene, even

reserved countenance. This unassuming Swedish woman was an international opera sensation in the nineteenth century. Our inability to hear her voice or

witness her dramatic power may explain why her fame has faded away.

Biographers who wrote tributes to the opera singer during her career

describe her performances with manifest emotion, giving us an indication of

her captivating presence on the stage. Known as the “Swedish Nightingale,” she began in

lower-class obscurity and rose to become recognized by royalty as an

indigenous treasure. On concert tours, overwhelming crowds thronged to greet

her arrival; and, after a show in London, even Queen Victoria threw a bouquet down to

her from the royal theater-box (Rosen). She remained humble in the midst of

celebrity and is esteemed alongside great women of prosopography for her

vocal talents as well as her charitable example—after retiring professionally, she gave free

concerts to raise donations for hospitals and the needy. Rediscovering her

through written accounts, along with a wealth of popular-culture materials,

including ephemera, cartoons and advertising campaigns, creates a picture of

an exceptional figure whose biography intersects with issues of class, the

arts in society, and public women.

In a biographical tribute written shortly after the singer's death, H. S. Holland and W. S.

Rockstro introduce their honorary subject with a comment about

her name which gives us a measure of the impression she made upon the

public:

Even the name of 'Jenny Lind' seemed to be inadequate to the

occasion. It is a name which English lips caress with affection, having in

it the sense and sound of some homely and endearing diminutive. But here,

one felt, was something more than affectionate diminutives could express;

something more than a delicious singer. . . something of a rare and majestic

type, which broke through the ordinary layers which encrust and imprison our

average human life. (6)

Here, the stature of the great woman seems out of proportion with the

public’s terms of intimate affection. Her rise to that stature is all the

more remarkable in light of the lack of love or “affectionate diminutives”

that she received during her neglected and impoverished childhood.

Johanna Maria Lind was born on October

6, 1820 in Stockholm,

Sweden, the daughter of working-class Niclas Jonas Lind

(1798-1858) and Anne-Marie

Fellborg

(1793-1856). She was considered illegitimate until age fourteen when

her parents were wedded, a second marriage for her mother.

Niclas, five years his wife's junior and only aged

twenty-two at Jenny's birth, was the unambitious son of a successful

lace-manufacturer, who failed in the business when it passed on to himself.

He held an unprofitable bookkeeping position and was unable to provide

enough income to support his family, but is described in biographies as

“good-naturedly weak; much given to music of a free and convivial kind”

(Holland and Rockstro 12). While Jenny may have inherited her father's

musical inclinations (he was an amateur singer in community festivals), she

certainly possessed none of his weakness of character. The single-minded

determination she later exhibited in training her voice for opera is a trait

to be found in her mother. Anne-Marie came from a respectable

family and was well-educated, qualities which enabled her to earn a living

as a schoolmistress when Niclas proved incapable of providing

for her. In 1820, she was running a day-school for girls out of

their home, where two of the students also boarded. Occupied with the

financial concerns of the household, the mother gave the new baby little

welcome and soon placed her daughter in the care of strangers.

Until

1824, Jenny lived in the countryside with a couple, a

parish-clerk and organist and his wife. While she was neglected by her

parents in early childhood, this was not an entirely unhappy period of her

life. Listening to the songs of wild birds, she felt an intense love for the

Swedish countryside that she retained even as an accomplished opera

singer—a national “instinct…native to the Swedes,”

according to biographers. The passion for “the country” had “deep-rooted

dominion” over Jenny Lind, and in turn she personified country folk.

She was in close touch with all that belongs to a simple

peasantry. She knew the tones of its songs; and the rhythm of its dances;

its simplicity, its charm, its pathos—all were hers. Something of its native

depth and dignity seemed to have passed into her. (Holland and Rockstro

13)

During her musical career as the “Swedish

Nightingale,” this indigenous quality was cherished by

international audiences of all ranks and the combination of homeliness and

powerful feelings which she displayed in performance was part of her common

appeal.

While Jenny's years in the countryside made a lasting impression, they were

short-lived. In 1824, she was brought back to town and for a

period of time, lived with her grandmother in a respectable almshouse for

the widows of Stockholm burghers. Here, she received affectionate care and

was taught a sense of religion and morality which guided her later charity

work. Her grandmother was the first to recognize the small child's musical

abilities, overhearing her one day at the piano and thereafter, her natural

talent was celebrated by neighboring widows who came to hear her sing.

Around 1828, her mother's day-school closed and economic

constraints once again disrupted Jenny's home-life. She was handed over to

the care of a childless couple who had placed an advertisement in the paper

for a child to come live with them. The husband was the steward and tenant

in the lodge-house of the same almshouse where her grandmother lived, so

happily, she was not removed from all familial relations when her mother

left Stockholm shortly after to take a governess position. However, in this

couple's guardianship, she spent many hours alone and a cat became the

audience for her songs. The clear, high voice carried to other ears, and one

of the people who heard from the street changed the course of Jenny's

life.

The

anecdote of her discovery is lovingly retold in nearly all biographies. The

version one presenter includes as having come from the singer's recollection

and recorded by her son, may be considered relatively authoritative:

Her favourite seat with her cat was in the window of the

Steward's rooms. . . and there she sat and sang to it; and the people

passing in the street used to hear, and wonder; and amongst others the maid

of a Mademoiselle Lundberg, [the principal] dancer at the Royal

Opera House; and the maid told her mistress that she had never heard such

beautiful singing as this little girl sang to her cat….[When] Mademoiselle

Lundberg….heard her sing, she said, 'The child is a genius; you must have her educated for

the stage.' (Holland and Rockstro 17)

Included in this version, but not in the one to follow, is the detail that it

was a maid who first appreciated the beauty of Jenny's voice before

Mademoiselle confirmed the discovery. One can speculate that the maid's

absence from other versions is due to the uncomfortable suggestion that a

lower-class person might have discerning taste, whether or not acquired in

service to an artistic mistress. Regardless of narrative intent, the maid,

when she is present in the story of Jenny's discovery, figuratively predicts

the appeal the singer had in her career to not only high, but low audiences,

as well. The tone of this version of the discovery is strikingly

different:

There was once a poor and plain little girl dwelling in a little

room, in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden. She was a poor little girl indeed

then; she was lonely and neglected, and would have been very unhappy,

deprived of kindness and care so necessary to a child, if it had not been

for a peculiar gift. The little girl had a fine voice, and in her

loneliness, in trouble or in sorrow, she consoled herself by singing. In

fact, she sung to all she did; at her work, at her play, running or resting,

she always sung.

The woman who had her in care went out to work during the day,

and used to lock in the little girl, who had nothing to enliven her solitude

but the company of a cat. The little girl played with her cat and sung. Once

she sat by the open window and stroked her cat and sang, when a lady passed

by. She heard the voice, and looked up and saw the little singer. She asked

the child several questions, went away, and came back several days later,

followed by an old music-master, whose name was Croelius

[singing-master at the Royal Theater]. He tried the little girl's musical

ear and voice, and was astonished. (Willis 5)

When the discernment of Jenny's talent originates with the lady, the story

can be placed in a neatly defined package. The woman of a better class

provides charitable assistance to one of the less fortunate class: a secure

hierarchy—as opposed to the destabilizing potential when a servant assists a

poor girl to rise to the level of renown that is recognized by royalty, her

name is on the lips of kings and queens. This presenter elects to replace

Jenny's name with “(poor) little girl,” and inflects the story with such

pathos that ones can see the tendency towards reducing her to “endearing

diminutives” which Holland and Rockstro suggest

obscured the public's recognition of her rare and intense artistic talent.

The maudlin affect veils the slippage between class and status

boundaries—what I consider to be the most critically significant part of her

biographical story—in the 'once upon a time' of fairy tales.

Although the

head of the Royal Theater of Stockholm nearly rejected Jenny when he saw

her—“a small,

ugly, broad-nosed, shy, gauche, under-grown girl!” (a

self-description from one of her letters)—she was accepted at the Royal

Opera School after he was moved to tears by her voice (Holland and Rockstro

18). There, she found her home on the stage. The Royal Theater assumed

guardianship of her and she was brought up, educated and received vocal

training at the expense of the government. By age ten, she made her first

appearance singing and dancing on stage and continued to play children's

parts in productions. Yet at adolescence, her voice changed; it lost the clarity

and high tone which had received so much praise. Several years passed before

Jenny would gain the chance to debut in the theater of Stockholm; however,

with determined study she mastered the new quality of her voice. Such a

trial would occur again at the height of the opera singer's career, when she

lost her voice and had to learn how to retrain it before she was able to

return to performing. Her commitment through this early ordeal signaled that

she had taken on singing as work. No longer the little girl who was

discovered to have such talent, Jenny Lind had claimed for herself the place

of a serious professional artist.

On March 7, 1838, audiences made a sensation of her performance

as Agathe in Carl Weber's

Der Freischütz. This was the first great role of

Jenny's many onstage triumphs and made her a favorite of the Royal Swedish

Opera. At age 20, she was accepted as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy

of Music and was appointed as a court singer to the royalty of Sweden and Norway. However, her popularity strained her

voice; over-exertion left it sounding harsh. Determined again to save her

musical powers, she traveled to Paris

seeking Manuel García, the famous baritone who became a vocal

instructor for the Paris Conservatory, and later, the Royal Academy of Music

in London. Before forbidding her to sing a note for three months, he

famously told her: “My

dear child, you have no voice. Or, you have had a voice and are just

going to lose it” (Lind-Goldschmidt 13). The period of silence

repaired her voice, and nearly a year's tutelage under García

saved the opera-singer's career. When Jenny returned to the stage, audiences

were not fickle to their one-time favorite, but immediately embraced her

again.

Not only was she appreciated in performance, but she was also welcomed in

literary and artistic circles of society. Though she lacked the beauty and

sophistication of the usual prima donna, she evidently blended in easily at

refined soirees, as an anecdote about her posing in a recreation of an

Italian Baroque painting at a party of fellow-artists suggests:

she appeared, at a Stockholm party, in a tableau-vivant, as

Carlo Dolce's St Cecilia [the patron saint of musicians]: and it was said

that she looked exceedingly like the picture: and she took special delight

in this personal resemblance to the Saint Cecilia; and after her death there

was found, among her private stores of little mementoes [sic], the rouge-card used at the tableaux, with her own writing on

the back to say that it had been given her by Fredrika Bremer as a memorial

of that evening. (Holland and Rockstro 85)

Along with novelist Fredrika Bremer, Jenny was intimate with

many significant figures of literature and music, including Hans

Christian Andersen, sculptor Georg Jensen, and

composers Mendelssohn, Chopin,

Meyerbeer, and A.F. Lindblad, “the Schubert of

Sweden” (Holland and Rockstro 4). Although she appeared

unsophisticated, the dramatic range of the roles she played mirrored a depth

of character which many found to be personally, as well as artistically,

engaging. These relationships showed her to be exceptional in several ways:

she was of the lower class yet many recognized an inherent sense of

refinement about her; she was a popular entertainer yet recognized by

cultured members of society as an artist of their own kind; and she was a

woman of the Victorian era publicly accepted into the company of men. One

biography notes the admiration Jenny's character won amongst serious minds:

“Its peculiar force lay in this—that it held enthralled the highest and best

minds in Europe. It was the men of genius who recognized in her something

akin to themselves” (Holland and Rockstro 4). In her late twenties, she was

inducted as the only female member of a student fraternity in Göttingen, Germany called

Burschenschaft Hannovera. Amongst the men of this classical German

organization she was fondly known as “Little Lady

Jenny”—endearing diminutives were attached to her name even as

she was distinguished from a commonly recognized form of femininity (Holland

and Rockstro 375).

For some of those who knew Jenny, esteem for her rare character and intellect

developed into romantic interest. Her fine grey eyes and sincere nature

captured the heart of Hans Christian Andersen when he met her during a

concert tour of Denmark, prompting him to write two of his most famous

stories in her honor, The Ugly Duckling and The Nightingale, the source of her stage name the

“Swedish Nightingale.” She was also an inspiration for

Mendelssohn as well as Chopin, both of whom

composed operas with her voice in mind. While nineteenth century biographies

acknowledge her professional relationships with these two men, a more

intimate association was not considered until new biographical information

surfaced that could unsettle some revered reputations. Professor

Curtis Price (formerly of the Royal Academy of Music in

London) claims in a recent biography on Mendelssohn that the married

composer was desperately in love with the singer. Price alleges that in

1847, Mendelssohn begged her to elope with him and

threatened suicide upon her refusal. A few months later, Mendelssohn was, in

fact, dead; however, this scandal of musical history remains a speculation

since the documents were sealed by an affidavit secured by Lind's husband in

1896. Jenny's requited romance with Chopin has been

publicly substantiated, though only very recently has it been discussed in

biography. Evidence shows that she obtained Queen Victoria's approval to marry him 1849. The

union never occurred because Chopin was fatally ill, but Jenny is said to

have sung at his bedside while the composer was dying. On February

5, 1852, while touring America, she married pianist Otto Goldschmidt (who had been one of Mendelssohn's

pupils), becoming a new bride at the rather late age of thirty-one.

Jenny's American concert tour greatly increased her fame, but her association

with P.T. Barnum, who financed the tour, had an unfortunate

impact on her reputation. Under the strain of continuous performance, the

exhausted singer was considering a transition to retirement, wanting to

commit herself to benefit appearances only. Barnum convinced her to make a

tour of America by promising that she would earn enough money to pay for her

retirement and fund her project of establishing several new schools in

Sweden. Counting on the extraordinarily high ticket sales of her tours in

Great Britain, the self-titled “Greatest Showman on Earth” introduced the

“Swedish Nightingale,” hitherto unknown by American audiences, in

advertisements touting her moral purity and social benevolence as much as

vocal talent. He began publicizing the tour half a year in advance of her

arrival, citing the free benefit concerts she had given as a promotional

tool to increase his profits from the 150 shows she was contracted for

(after 93 performances, she ended their agreement). While Jenny donated

nearly all of the $250,000 she made during the tour, Barnum's commercial

exploitation muddied what, for her, was a genuinely altruistic use for her

immense celebrity. Critics focused on the spectacle made of and by her in

the United States and her charitably intended tour was repeatedly parodied

in the press.

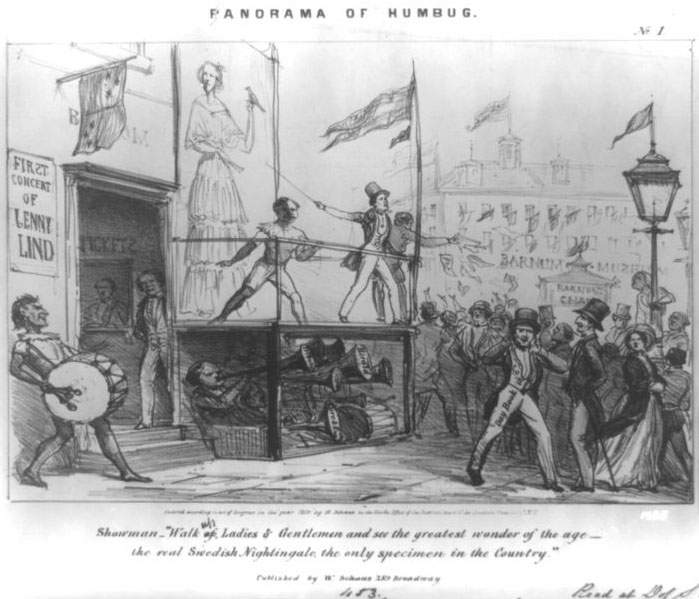

A cartoon by New York engraver William

Schaus entitled “Panorama of Humbug” (1850) satirizes the extent

of the advertizing campaign that Barnum orchestrated to launch the “Swedish

Nightingale” to popularity before she even sang a note for an American

audience.

[1] It shows the public frenzy

that greeted her arrival being created by showmen campaigning on the street

as Barnum watches from behind a curtain in an inconspicuous corner of the

picture. A colossal image of Jenny, nightingale perched in hand, dominates

the background and immediately draws our eye to her; an optical effect which

ironically mimics the humbuggery being scrutinized. The cartoon shows the

friction between her marketability as an eminent figure and her efforts to

make philanthropic use of her eminence. At the same time, her hugeness in

the picture suggests another reading: that Barnum's puffery as unnecessary

because the reputation which earned her such public stature served as its

own advertisement.

The approval Barnum generated for the singer before

audiences even heard her voice corroborated claims from across the Atlantic

that the taste of the American public was guided by popular opinion rather

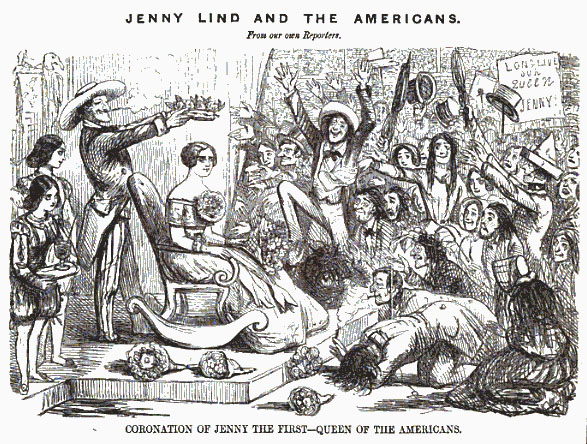

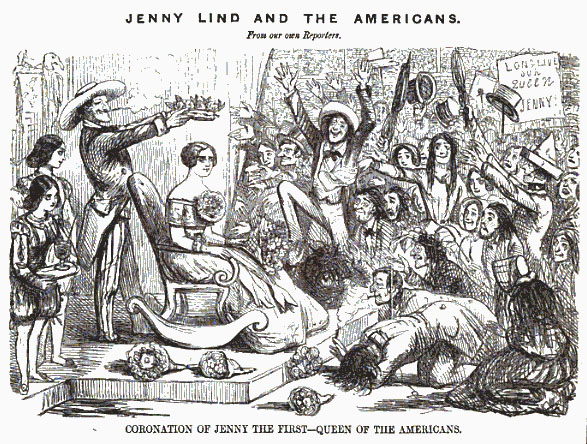

than refined discrimination. A cartoon called “Coronation of Jenny the

First—Queen of the Americans” (1850) which appeared in

Punch is a satirical comment upon the lack of sophistication

amongst her American fans.

[2] Before a raucous

and apparently low-classed crowd of people, some prostrate in homage, some

whooping and leaping, sits Jenny, being crowned as their popularly elected

Queen. Paradoxically, the reference to her royal associations reminds us

that the high shared their appreciation of her with the low, challenging the

association between lack of taste and lack of status. As though she were

Victoria, whom the cartoon rendering immediately calls to mind, Jenny's

countenance is as gravely sober as if she were being charged with royal

responsibilities. Imaging her as a double for Victoria (even though it was

intended to be a parody) encourages us to consider these two women

collectively, as both were in highly public positions at the same time as

they were figures of feminine virtue for an emerging middle-class

ideology.

The effect of collecting forms of womanhood is present in another cartoon

titled “To Jenny Lind, From Punch,” which makes satire of one of the only

public roles that Victorian women could engage in without compromising their

femininity: charity work. Jenny is shown in the middle of the picture

holding a basket of food—an object symbolizing the charitable woman's

mission. She stands in a Madonna-like pose, her eyes are downcast, her arm

and hand extended to comfort the impoverished crowd of shoeless wretches and

mothers bearing infants, who kneel in a circle at her feet. This exaggerated

portrait of the ministering angel parodies Jenny's philanthropic activities;

yet at the same time, the cartoon's figure for satire runs up against

prosopography, which uses the same topos image to present genuinely worthy

heroines as models for women's public contributions. Many of the ministering

figures found in collected biography shared the mission of charity work and

Jenny, who donated concert proceeds to Florence Nightingale's Nursing Fund at the end of the Crimean

War, provides us with an example of one heroine supporting a cause

championed by another.

Although she continued to give performances to raise money for the needy,

Jenny retired from her professional stage career when she completed the

concert tour of America in 1852. The Goldschmidts settled into

the calm of domestic life and raised two sons, Walter and Ernest, and a daughter who shared the same

endearingly diminutive name as her mother. In 1883, Jenny gave

her last charitable performance and during the same year, her vocal talent

received one more public acknowledgment when the Prince of Wales appointed

her as the first professor of singing at the newly established Royal College

of Music. On

November 2, 1887, Jenny died of cancer at her home in

Wynd's Point, England. Although this phenomenal celebrity of the nineteenth

century has been largely forgotten today, evidence of her popularity is

preserved in an incredible amount of material culture from the era. Her name

and image can be found on everyday items from cigar boxes, hard liquor,

perfumes, plate ware, tea sets, furniture, pastry recipes, even train cars.

Jenny's legacy as a professional artist earned her a place in high culture

alongside her male peers. Near Handel's statue in Poet's Corner at Westminster

Abbey, a plaque is dedicated in honor of her musical accomplishments.

Notes

1 William Schaus, “Panorama of Humbug” (New

York: W.Schaus, 1850).

2 “Coronation of Jenny the First—Queen of the

Americans.” Punch 19 (1850): 146.

Works Cited

Holland, Henry Scott, and William Smyth Rockstro. Memoir of Madame Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt: Her Early

Art-Life and Dramatic Career, 1820-1851. Vol. I &

II. London: J. Murray, 1891.

Lind-Goldschmidt, Johanna Maria. Memoir of Jenny

Lind. London: John Olliver, 1847.

Rosen, Carole. "Lind, Jenny (1820–1887)." Oxford

Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew

and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004.

Willis, Nathaniel Parker. Memoranda of the Life

of Jenny Lind. Philadelphia: Robert E. Peterson, 1851.