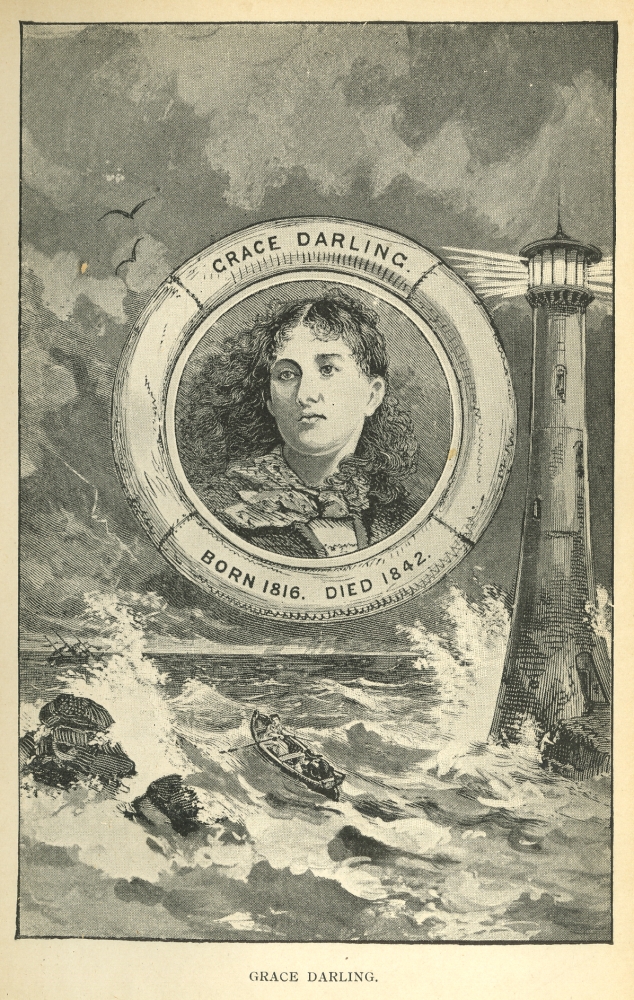

At the dawn of the Victorian Era, one diminutive but brave young woman

captivated the national consciousness as a result of her role in a dangerous

rescue mission off the coast of Northumberland. Her name was Grace

Darling, and through her efforts in the rescue of nine

shipwrecked passengers early on the morning of September 7,

1838, she was transformed into an exalted national hero. She was

both lauded and hounded by the public up until her early death, after which

she, and her story, continued to entrance the public imagination in Britain

and abroad.

At the dawn of the Victorian Era, one diminutive but brave young woman

captivated the national consciousness as a result of her role in a dangerous

rescue mission off the coast of Northumberland. Her name was Grace

Darling, and through her efforts in the rescue of nine

shipwrecked passengers early on the morning of September 7,

1838, she was transformed into an exalted national hero. She was

both lauded and hounded by the public up until her early death, after which

she, and her story, continued to entrance the public imagination in Britain

and abroad.

Grace Horsley Darling was born in Bamburgh, Northumberland on November 14, 1815, and was the

seventh of William and Thomasin Darling’s nine

children. William Darling was a lighthouse keeper, as his

father had been before him, and Grace

and her siblings grew up on the “Longstone Light on one of the wild and

savage Farne islands”

(Sitwell 59). Relatively little is known regarding Grace’s early years, though she seems to

have received a solid education evident in her handwriting, which was “equal

to that of most ladies” (Bruce 376). Furthermore, she was

surrounded by books, albeit those “principally [of] Divinity” and

“Geography, History, Voyages and Travels, with Maps” (Mitford

89). Her father regarded novels and other forms of literature, as well as

pursuits such as card-playing, to be the works of the Devil, and raised his

family within the confines of strict Puritanism (Mitford 89;

ODNB ).

In their remote location, Grace and her

family were isolated from society at large, making only occasional

excursions to the mainland, and otherwise occupying themselves with the

daily domestic duties of the lighthouse (Bruce). Perhaps as a

result of this confined but (for Grace,

apparently) enjoyable upbringing, Grace

was “remarkable for a retiring and somewhat reserved disposition”

(Bruce 376). She assisted her father in his work on the

lighthouse and kept watch at times (ODNB), bearing witness to several wrecks

and rescues over the course of her lifetime but never participating in them,

as her older brothers were always present to help their father

(Bruce).

In this manner, for the first twenty-two years of her life, the mild-tempered

“young girl of five feet two, with small wrists” (Sitwell 61)

lived quietly in a household of sober industry and religious commitment. The

events of the early hours of September 7, 1838, however,

drastically expanded the confined world in which Grace lived, though they never seemed to

change her fundamental personality and temperament.

The Forfarshire, one of the largest steamships of its day, set off from port

on September 6, 1838, carrying around sixty people, crew and

passengers. Upon encountering a brutal storm near the Farne Islands, the ship was wrecked on Big Harcar

Rock (Mitford 29). Grace,

keeping watch from the lighthouse, glimpsed the nine survivors at around

five o’clock on the morning of September 7 and informed her

father (Thomasin Darling). Her older brothers had all left

their parents by then to live on the mainland, while her younger brother,

who was usually present at the lighthouse, was away on a fishing excursion

(Mitford 29). As a result, Grace was put in the unusual position of being the only

able-bodied assistant for her father. Most initial accounts of the story of

this day portray William Darling as reluctant and unwilling to

brave the stormy waters, while Grace

forced him into action by declaring her intention to go regardless of his

participation (Sitwell). Later accounts, however, have

questioned this depiction of the story, and the only firsthand written

account of the rescue is that of William Darling himself, in

the official letter he wrote to the Secretary of Trinity House.

His depiction of the rescue is a straightforward factual representation in

which he credits his “Daughter” with having “observed a vessel on Harker’s

Rock” and “incessantly [applying] the glass until near 7 o’clock when, the

tide being fallen [they] observed three or four men upon the rock.” He then

states that they “agreed that if [they] could get to them some of them would

be able to assist [them] back,” after which they “immediately launched

[their] boat, and [were] enabled to gain the rock.” Grace and William then

returned to the Lighthouse with the sole woman and four of the men, two of

whom then returned with William to retrieve the remaining four

men (William Darling). The matter-of-fact attitude with which

these events were treated by the Darling family is evident in

William Darling’s account of the rescue. To a family of

lighthouse-keepers, dangerous rescues were fairly frequent occurrences, and

the efforts that Grace and her father

put forth were expected and unremarkable. Indeed, William Darling is likely

to have thought of the prospect of "sole salvage rights" to the goods in the

wreck if he could reach the ship (ODNB). The rest of the nation, however,

did not perceive the event in such a pragmatic manner. Instead, the public

exalted the romantic and heroic nature of the event in a manner directly

opposed to the down-to-earth humility of the Darlings’

reaction.

The year 1838, one

year following the beginning of Queen

Victoria’s reign and its corresponding era, was a “moment [that]

was opportune for acclaiming female virtue” (Correspondent). Although Grace and her father played equally

significant roles in the rescue of the survivors, it was Grace and the combination of her

unconventional physical feat and virtuous humility, emblematic of ideal

Victorian womanhood, that attracted the media and publicity. The number of

visitors at the Longstone Lighthouse increased exponentially as people from

all over the country flocked to meet the great heroine and see the location

of her selfless deed.

In addition to the masses that besieged the once reclusive world of Longstone

Lighthouse, numerous institutions celebrated the Darling

family. The Royal Humane Society acknowledged Grace and William Darling in a special general

court held on October 31, 1838 that highlighted the

“intrepidity, presence of mind, and humanity that nobly urged

[Grace]” to rescue the survivors of the shipwreck

(Thomasin Darling 26). In addition to this acknowledgment,

Grace and William each

received the society’s Golden Medallion, one of the highest honors of that

time. The Duke of Northumberland was

chosen to deliver the honorific medallions, and he added to the delivery his

own gifts for the family: waterproof clothing, a silver teapot, a gold seal

engraved with Grace’s initials, and

four pounds of tea. It was through this act of largesse that the lifelong

friendship between the Duke and Grace

began (Thomasin Darling).

Following the Royal Humane Society’s lead, many other national and local

institutions recognized Grace’s

actions. She received medals from The Royal Institution for the Preservation

of Life from Shipwreck, The Edinburgh and

Leith Humane Society, The Glasgow Humane Society, and The Shipwreck

Society of Newcastle. Some organizations,

such as Lloyds, the insurance company, and The Ladies of Edinburgh, chose to send money and stocks to Grace and her father. Just a year after

the shipwreck, Grace had received about

seven hundred and fifty pounds' worth of stock (Thomasin

Darling).

Medals, stocks, and money were not the only gifts that Grace and her family received. Admirers

sent a plethora of treasures that included silver tea sets, jewelry, and

even a beaver bonnet. The number of presents received by the family, despite

its immensity, was insignificant in comparison to the number of letters sent

to the lighthouse. Many people wrote simply to praise Grace, demonstrating the public

fascination surrounding her. Others wrote to describe how they had lost

loved ones in shipwrecks and to thank Grace for preventing others from suffering the same loss. Queen Victoria herself recognized and

contributed to Grace’s national

prominence when the Darlings received a letter from the United Kingdom’s Treasury stating that

“Her Majesty [had] been called to the circumstances attending the Wreck of

the Forfarshire Steamer” and wished to acknowledge Grace Darling for her actions in saving

the survivors (Thomasin Darling 30). Amongst all of these

letters, however, there is no evidence that Grace ever received acknowledgement from the survivors of the

Forfarshire’s wreck (Thomasin Darling).

Grace attempted to reply to every letter

and gift she received. She usually declined any admiration or gratitude,

insisting that she was simply God’s instrument, and that therefore it was

God who deserved the thanks. Many people wrote to Grace asking for a signature or lock of

her hair, leading her to begin enclosing locks of hair in her responses as a

means of repayment for the recognition she received (Thomasin

Darling). This custom soon ended, however, as Grace “would soon have been left with a

closely cropped head” had her attempts to satisfy the demanding public

continued in this manner (Thomasin Darling 47).

Despite this sudden burst of popularity and fame, Grace “shrank from, not courted, the

public” (Thomasin Darling 38), behavior that simultaneously

reinforced the Victorian conception of her virtuous nature and characterized

her as a shy and wild creature threatened by the hungry public

(Sitwell). Grace

received many offers to be properly introduced to London’s society, some including paid appearances, but

she refused all of them. The Duke of Northumberland, now a family friend and patron, understood Grace’s reluctance to embrace her fame

and worked to spare her from undesired exhibition. When Grace received letters requesting her

appearance at various ceremonies and functions, she informed the Duke and he

wrote politely worded refusals on her behalf. Eventually, people began to

write to the Duke in order to pass messages on to Grace. Grateful for this understanding

and help, Grace called the Duke her

Guardian and herself his servant (Thomasin Darling).

The Duke was not able to shield Grace

from the artistic community, however. The events of that September morning

seized the artistic imagination of the era, and painters such as J.W.

Carmichael and Thomas Musgrave Joy requested that

Grace and her father sit for

portraits. Many times, Grace would be

forced to reenact awkward positions in order for the painters to properly

portray the scene of the Forfarshire’s shipwreck. There were also many books

dedicated to Grace’s story. Many of

them were written as romances, with loose treatment of the facts of the

event. William Wordsworth commemorated Grace and her actions in verse considered

to be beautifully and poetically written, but also greatly romanticized and

“embarrassing” (ODNB). Grace did not

read or pay attention to any of the novels, in keeping with her strict

upbringing (Thomasin Darling).

She continued to “politely refuse” all offers of paid appearances

(Correspondent) and to decline invitations to enter into London society, as Grace was content to focus on her chores and duties at Longstone

and to remain a companion and helper to her parents. She refused numerous

offers of marriage following her rise in fame (Bruce), and

“clung to her father and to her name, [explaining] that any husband of hers

should take it” (Thomasin Darling 11). She showed no

indications of yearning for something more than what she had, and refuted

the assumption that her quiet life on the island was unfulfilling, stating

that she “[had] no time to spare” as she had “seven apartments in the house

to keep in a state fit to be inspected every day by Gentlemen, so that [her]

hands [were] kept very busy” (Mitford, 89 and 90). Despite the

external clamor and demands of the public, Grace was satisfied with the quiet confinement, humble industry,

and familial duty of the lighthouse.

In this way, Grace lived contentedly at

the Longstone Lighthouse until a sudden decline in her health occurred after

a visit to her oldest brother on Coquet

Island in 1842. In the hope of improving her condition, Grace’s parents sent her and her sister,

Thomasin, to visit a family friend, George

Shield, in Wooler

(Thomasin Darling, Britain Unlimited). While there, Grace wrote to her parents that she

greatly enjoyed spending time with her sister and was beginning to feel

better. Thomasin’s letters contradicted Grace’s claim, however, as she wrote that

her sister’s coughs remained about the same (Thomasin

Darling).

The two sisters then went to Alnwick, the

residence of the Duke of Northumberland,

as the Duke had requested that Grace be

treated by his personal doctor. Grace’s

health never improved, however, and the doctor said that her disease was one

which “no skill, nor care, nor kindness could arrest” (Thomasin

Darling 56). In one last attempt to save their daughter, the

Darlings sent Grace to

Thomasin’s home in Bamborough. Much to everyone’s surprise, Grace began to show signs of increasing

health within the first few days in Bamborough. Despite this short-lived hope, Grace died several days later on

October 20th, 1842 at the age of twenty-seven, a victim of

what is believed to have been tuberculosis (Thomasin Darling,

Britain Unlimited). She was buried in St. Aidan’s Churchyard, less than one

hundred yards from where she had been born (Britain Unlimited).

Though Grace was dead, her fame lived on

in literature, art, popular culture, and, most significantly, the national

consciousness. As Edith Sitwell put it, “to the last day of her

life Grace Darling could not see that

she had done anything extraordinary…but she became the pride of the nation”

(Sitwell 62). Certain types of heroic legend coincided in

her, as in the physical courage and prowess of Joan of Arc, the wild, indigenous innocence and rescue of Pocahontas or Walter Scott's heroines, and

other romantic themes apart from love and marriage. In turn, she became a

type recognized in other women's deeds around the world, even for

predecessors such as the "Grace Darling of Newfoundland," Ann

Harvey, who helped to rescue 180 survivors of a shipwreck in

1828 (Ann Harvey). To the Victorian Era, Grace stood as an emblem of both British courage and female virtue that

resonated deeply with that era's imperialism and idealism. She was a woman

with a truly “English heart”

(Mitford) who represented the absolute best of her society,

and gave its members hope and faith in a time of transition.

Works Cited

Ann Harvey's Weblog

, http://thedespatch.wordpress.com, 8 August 2009.

Bruce, Charles. The Book of English Noblewomen: Lives Made Illustrious by Heroism, Goodness,

and Great Attainments. W.P. Nimmo, 1875, pp. 375-385. Google Books. 10 Nov

2008.

http://books.google.com/books?id=HR8XAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA375&dq=Grace+

Darling+date:1815-1899& lr=&as_brr=0#PPA378,M1

Correspondent. “The Centenary of Grace

Darling: A Nation’s Acclamation,” The Times 07 Sept

1938. The Times Digital Archive, Infotrac, Gale Group. 3

Nov 2008.

http://infotrac.galegroup.com/itw/infomark/64/55/46060710w16/purl=rc1_TTDA_0_CS

253309735&dyn=13!xrn_24_0_CS253309735&hst_1?sw_aep=viva_uva

Darling, Grace. “The Wreck of the

Forfarshire: A letter from Grace

Darling,” The Times 20 Oct 1838.The Times Digital

Archive, Infotrac, Gale Group. 3 Nov 2008.

http://infotrac.galegroup.com/itw/infomark/64/55/46060710w16/purl=rc1_TTDA_0_CS

51014484&dyn=3!xrn_1_0_CS51014484&hst_1?sw_aep=viva_uva

Darling, Thomasin. Grace

Darling, Her True Story. Paternoster Row, London:

Hamilton, Adams, & Co., 1880. Google Books. 1 Nov 2008.

http://books.google.com/bookshl=en&id=bAUoQC0ryeoC&dq=grace+darling+her+true

+story&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=3rcg0yXrpt&sig=6FCSfboxaRzIQV273

B1WfXu4M8c&sa=X&oi=book_result&-Secretary-of-Trinity-House.html

“Grace Darling.” 2002-08. Britain Unlimited. 1 Nov. 2008.

http://www.britainunlimited.com/Biogs/Darling.htm

H. C. G. Matthew. “Darling,

Grace Horsley (1815–1842).” 2004. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford

University Press. 1 Nov. 2008.

http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/7155

Mitford, Jessica. Grace

Had an English Heart. London: Penguin Books Ltd., Butler and Tannner Ltd.,

1988.

Sitwell, Edith, Dame. English Women. London: Prion,

1942.

pp.59-63.