In 1853, the

twenty-eight-year-old Adelaide Anne

Procter wrote a letter describing a peasant’s engagement party

she had attended in Italy:

In 1853, the

twenty-eight-year-old Adelaide Anne

Procter wrote a letter describing a peasant’s engagement party

she had attended in Italy:

"We have been to a ball, of which I must give you a description. Last

Tuesday… we heard very distinctly a band of music, which rather excited my

astonishment… Emily said, ‘Oh! That band is playing at the

farmer’s near here. The daughter is fiancée to-day, and they have a ball.’ I

said, ‘I wish I was going!’ ‘Well,’ replied she, ‘the farmer’s wife did call

to invite us.’ ‘Then, I shall certainly go,’ I exclaimed… We were received

with great enthusiasm; the only drawback being, that no one spoke French… I

began to be afraid that some idea of our dignity might prevent my getting a

partner; so, by Madame B.’s advice, I went up to the bride, and

offered to dance with her… My [other] partner was a little man, like

Perrot, and very proud of his dancing. He cut in the air

and twisted about, until I was out of breath, though my attempts to imitate

him were feeble in the extreme… after seven or eight dances, I was obliged

to sit down. We stayed till nine, and I was so dead beat with the heat that

I could hardly crawl about the house… it is so long since I have danced.”

–Dickens, xvii-xix

Adelaide Anne Procter’s exuberance in

this anecdote conflicts with the general impression of a severe or

meditative character, reflected in her role as a poet, advocate for women’s

rights, and member of a prominent literary family. A friend of the family

described the young Procter as

possessing a “doomed” look about her, manifested in a “marked brow over

heavy blue eyes" and a “mournful expression for a little child”

(Gregory, Life and Work [LW], 5). However, Charles

Dickens provides us with a contrasting view of Procter’s character as he writes that

even on her deathbed “her old cheerfulness never quitted her”

(Dickens, xxiii). Though Dickens proved to be

a prominent advocate for Procter and

her works, one must wonder what he saw in the young lady that few others

did. These markedly different perceptions of Adelaide Anne Procter’s personality

only begin to relate all the ways she was, and is today, perceived by

critics and friends alike.

Adelaide was born into the

Procter family in London

on October 30, 1825, and she “grew up amid surroundings

calculated to develop her literary taste” (Lee, 1). Many family

friends perceived that she had a serious demeanor, as they would have

expected of the daughter of a well-respected poet. Her father, Bryan

Waller Procter, who published under the name Barry

Cornwall, was a lawyer and a poet so well regarded that he has

prominent placement in several short obituaries of his daughter. Procter’s mother encouraged her

daughter’s interest in poetry by copying poems into a small album, which the

young girl carried “about like another little girl might have carried a

doll” (Dickens, xvi). Procter grew up surrounded by important figures of literature

and reform, such as William Makepeace Thackery, Charles

Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, and M. P. Benjamin

Leigh Smith (Hoeckley, 2); however, as her

experience at the engagement party documents, she also enjoyed associating

with people outside her elite circle, and took pleasure in non-literary

pursuits.

Despite Procter’s familiarity with

the literary world, she refused to rely on her connections as she sought

publication. She even submitted her poetry to Dickens’

publication, Household Words, under the pseudonym “Miss

Berwick” (2). Her use of a female name (unlike authors such as

Marian Evans and the Brontë sisters who used masculine pen names) can be seen as an

early indication of her later campaigns for women’s rights, becaue she

promoted women’s entrance into the male-dominated sphere of publication.

Dickens himself was unaware that Miss Berwick,

whose poetry he frequently published, was actually Adelaide Anne Procter, the daughter of

a long-time family friend. One winter day in 1854, as he visited with the

Procter family, he warmly praised the unknown female poet

whose work he had been publishing for two years (2). The following evening,

he learned that he had been praising “Miss Berwick” in her

presence (2). Until then, Dickens and the Household Words staff

had fantasized that this mysterious Miss Berwick was a

governess. He had so fully invented her character that his “mother was not a

more real personage to [him], than Miss Berwick the governess

became” (Dickens, xiv), but he transferred his admiration for

“Miss Berwick” to Miss

Procter. Her use of a pseudonym “strikingly illustrates the

honesty, independence, and quiet dignity, of the lady’s character” (xiv-xv)

because she relied on her talent, rather than her connections, to advance

her art.

Dickens’ appreciation for Procter’s poetry continued after he discovered her identity, and

over time she became his most published author (Gregory, A. Procter, 1). Dickens

published her poetry not only in Household Words, but also All the Year

Round, another of his well-circulated periodicals (Hoeckley, 2;

Lee, 1). Although very few periodicals besides

Dickens’ featured her work (Drain, 2), she had

ample opportunity to publish her poetry through Dickens. She

was the only poet whom he featured in his Christmas edition.

(Gregory, LW, 228). She published her own two-volume book

of poetry, Legends and Lyrics, in May of 1858, and both volumes were reprinted

in multiple editions.

Although Procter found professional

success as an artist, her poetic ability is only one of many traits

distinguishing her from most Victorian women. She was raised as a

Protestant, but she and her sisters converted to Catholicism in 1851, possibly influenced

by an Italian aunt (Hoeckley, 2). This conversion is

significant: given the strong anti-Catholic sentiments throughout England at this time, her conversion

shows strength of character. Some scholars speculate, however, that she had

already secretly adopted Catholicism two years earlier (Drain,

2), when she was twenty-four. Adelaidemay have waited to announce her decision until she had

her sisters’ support because her conversion complicated the initially strong

relationship between herself and her father (Gregory, LW, 10).

But whether she feared cultural or familial disapproval, her delay may

detract from her iconic position as an independent woman. However, her

Catholic faith led her directly to passionate involvement with social work,

arguably one of her most progressive achievements.

Because of widespread bigotry against Catholics, Procter’s conversion aligned her with

oppressed sectors of society, including working-class Irish Catholics (11). She supported the Providence

Row Night Refuge, which aided predominantly Catholic homeless women and

children (11). Her concern for the disenfranchised also led her to the

struggle for women’s rights, a cause she championed throughout her life. She

associated with other women who combined their artistic and cultural

interests with the advancement of women’s causes. These women frequently met

in each other’s homes to discuss marriage and property laws in the context

of women’s lives (Hoeckley, 3). Though they often met sexist

criticism meant to trivialize their cause (3), that attention also indicated

that their ideas posed a threat to the societal status quo.

Procter used her success as a poet to

advance the causes for which she fought. Beyond writing for personal

enjoyment, she also dedicated her literary efforts to helping women in the

workplace. She united her passions for writing and reform through her work

in The English Woman’s Journal, which

fought for women’s equality in education, employment, and property rights

(3). She used her poetic skills to provide a voice for the Catholic widows

and orphans she was helping through the Providence Row Night Refuge. While

working to support the Society to Promote the Employment of Women (SPEW),

she published

Victoria Regia: a Volume of Original Contributions in

Poetry and Prose

(3-4). This publication supported the cause of female employment by

using a printing company which exclusively employed women (4). Procter’s poetic success was not only

a personal victory, but also a way for her to advance her belief in social

justice.

Despite her prolific publication, critical reception of her poetry was and

remains highly ambivalent. Even Dickens, Procter’s most enthusiastic advocate,

was uneasy about the social aspects of her poetry. While declaring his

admiration for her style, he evinced some apprehension about those social

aspects (Gregory, LW, 197). He praised her philanthropic work

but avoided mentioning her official positions within liberal organizations

(197). Beyond her possibly controversial topics, a contemporary biographer

writes that her style of poetry was often “not only sentimental but also

formally simplistic” (Hoeckley, 5). Procter

herself admitted that “Papa is a poet. I only write verses”

(Drain, 3). Despite its formal uninventiveness, her poetry

was popular because of its “invariably simple and direct language and

strongly affective rhetoric. This simplicity… masks a complexity of thought

and feeling” (Gregory, LW, 3-4). Critiques of her work,

accompanied with Procter’s own

humility, suggest that her poetry’s significance comes from its content

rather than its form or style.

Procter’s relationships within

feminist societies have led to speculations about her sexuality. Little is

known about her romantic and sexual liaisons. She was engaged at least once,

according to a letter from William Makepeace Thackeray, and

there is additional evidence that she was engaged to a man who devastated

her by breaking the engagement (21, 24). This latter incident probably

occurred two years before the Thackeray letter, although the

dating and details are so uncertain that this may be the same man (21, 24).

Despite these documented heterosexual relationships, rumors of her

lesbianism have persisted. Her friendship with Matilda M. Hays,

a co-editor of The English Woman’s

Journal, may not have been platonic: “She dedicated the ‘First Series’ of

Legends and Lyrics to ‘Matilda M. Hays’. On the 23

January 1858

Procter wrote a poem titled ‘To

M.M.H’…It is a poem which expresses love for Hays… who dressed

in men’s clothes and had lived with [a woman] in Rome” (24-25). Other than the vaguely erotic nature of several of

her poems (254), there is little evidence about her romantic or sexual

life.

The intense activity and ceaseless work that made Procter remarkable contributed to her

early death at the age of thirty-eight. She was confined to her bed for the

last fifteen months of her short life as she suffered from tuberculosis. It

is highly possible that her work among the sick exposed her to the

tuberculosis that killed her, although her intense work ethic rendered her

physically ill-equipped to fight the disease (Hoeckley, 5). She

died in the presence of her mother and sister in London at the age of thirty-eight (Dickens,

xxiv).

Despite her passionate activism, her obituaries hailed her importance as a

poet and as her father’s literary heir. Her obituary in The Examiner lists

her poetic achievements with no mention of her social importance (The

Examiner). It fallaciously states that she died unexpectedly, despite her

fifteen months on bed rest (The Examiner). Her obituary in Liverpool Mercury Etc. falsely reports that she died “at

about thirty years of age” (Liverpool).

Both of these inconsistencies romanticize her premature death. In another

obituary, published by an Irish

newspaper, Procter’s Catholic faith

is celebrated above her achievements; the author claims that “The religious

no less than the literary world has good cause to lament [her] loss”

(Freeman’s). These early accounts of her life omit her social reform, while

contemporary biographers emphasize her importance as a woman’s advocate

above her merit as a poet. As society has recognized the importance of

women’s rights, this aspect of Procter’s life has been more celebrated. These different

perceptions are possible because Procter was such a rich character, with a young woman’s

cheerfulness, a poet’s intensity, an artistic vision, and a passion for

reform.

Works Cited

“Adelaide Anne Procter.” Freeman’s

Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser [Dublin, Ireland] 20

February 1864

“Births, Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries.” The Examiner [London, England]

6 February 1864: Issue 2923.

Dickens, Charles. Introduction to The Complete Works of Adelaide A. Procter. London: Chiswick Press, 1905. Google Books.

http://books.google.com/books?id=274RAAAAYAAJ&dq=charles+dickens+adelaide+anne+Procter&

printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=nb4M_PKtq9&sig=Xn-lFf6C6pGy5kZpPbeFFT4q9gs&

hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=3&ct=result#PPP1,M1.

Drain, Susan. From Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume

32: Victorian Poets Before 1850. Mount Saint Vincent University, 1984. “Adelaide Anne Procter.” Literature

Resource Center. UVA Libraries. 9 November 2008.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/LitRC?vrsn=3&OP=contains&

locID=viva_uva&srchtp=athr&ca=1&c=1&ste=6&tab=1&tbst=arp&ai=U13717035&

n=10&docNum=H1200003496&ST=Adelaide+Procter&bConts=4202685.

Gregory, Gill. The Life and Work of Adelaide

Procter. Great Britain,

Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1998.

---. “Procter, Adelaide Anne.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Oxford University Press, 2004-2008. 9 November

2008.

http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22834?_fromAuth=1.

Hoeckley, Cheri Lin Larsen. From Dictionary of Literary

Biography, Volume 199: Victorian Women Poets. Westmont College, 1999. “Adelaide Anne

Procter.” Literature Resource Center. UVA Libraries. 9 November

2008.

http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/LitRC?vrsn=3&OP=contains&

locID=viva_uva&srchtp=athr&ca=1&c=2&ste=6&tab=1&

tbst=arp&ai=U13717035&n=10&docNum=H1200008287&

ST=Adelaide+Procter&bConts=4202685.

Lee, Elizabeth. “Procter,

Adelaide Anne.” Oxford

Dictionary of National Biography Archive.

“Railway Traffic.” Liverpool Mercury etc.

[Liverpool, England] 6 February 1864; Issue

49

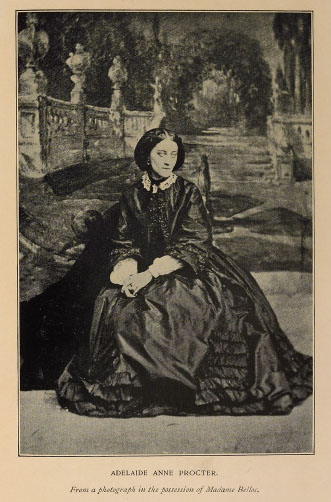

Photograph Sources

“Adelaide Anne Procter.” Adelaide Anne Procter. 16

November 2008.

http://gerald-massey.org.uk/procter/index.htm.

“Adelaide, from a painting by

Emma Gaggiotti Richards.” The Parents of Adelaide Procter. 16 November

2008. http://gerald-massey.org.uk/procter/b_biog.htm.

“Charles Dickens.” Charles Dickens: An

Introduction to Legends and Lyrics by Adelaide Anne Procter. 16 November 2008.

http://gerald-massey.org.uk/procter/b_biog.htm.

“Matilda Hays.” Adelaide

Anne Procter. 16 November 2008.

http://gerald-massey.org.uk/procter/index.htm.