Hannah More was the fourth daughter of

Jacob More, village schoolmaster of Lord Bottelourt’s

foundation-school at Stapleton, and

his wife; but this same daughter was destined to become

world-famous, and to bring countless visitors into the neighbourhood of Bristol, both during her life and after

her death. At eight years old we see little Hannah the happy possessor of a

long-coveted "whole quire of writing-paper," which it had not needed much

coaxing for her to obtain from her observant mother. Mrs Jacob

More was

one of Nature's gentlewomen, and though only a farmer's daughter, she was a

person of vigorous intellect, who fully appreciated the value of education,

and had made the most of her own rather narrow possibilities. Bearing in

mind the efforts of her later years, it is interesting to notice

that Hannah More's first attempts in religious literature were letters to

imaginary people of depraved character and their replies thereto, full of

contrition and promises of amendment!

Hannah More was the fourth daughter of

Jacob More, village schoolmaster of Lord Bottelourt’s

foundation-school at Stapleton, and

his wife; but this same daughter was destined to become

world-famous, and to bring countless visitors into the neighbourhood of Bristol, both during her life and after

her death. At eight years old we see little Hannah the happy possessor of a

long-coveted "whole quire of writing-paper," which it had not needed much

coaxing for her to obtain from her observant mother. Mrs Jacob

More was

one of Nature's gentlewomen, and though only a farmer's daughter, she was a

person of vigorous intellect, who fully appreciated the value of education,

and had made the most of her own rather narrow possibilities. Bearing in

mind the efforts of her later years, it is interesting to notice

that Hannah More's first attempts in religious literature were letters to

imaginary people of depraved character and their replies thereto, full of

contrition and promises of amendment!

The

evangelical piety of Hannah More is rather remarkable, when one considers

that her father was a staunch Tory and High Churchman.

Perhaps it would be more correct to say that it seems remarkable at first

sight; for it has been noticed that a Nonconformist strain is frequently

productive of conspicuous piety in the families of High Church religionists.

Three generations had passed since the time when Jacob More's

ancestors had fought bravely as captains in Cromwell's army,

and it is probable that the precocious child heard many stirring stories of

their doings in the time of the Commonwealth, which intensified the personal and fiery interest

with which she afterwards watched the Revolution of 1793. "Coming events cast their

shadows before," and the nursery floor was

often the stage whereon, in carriages made of their high-backed chairs, the

child played at excursions to London,

and drove with her sisters "to see Bishops and Booksellers"—a curious

combination, when one remembers the happy experiences which

she subsequently enjoyed with Porteous and

Cadell.

The following quaint advertisement occurs

in the Bristol newspapers of

March 11, 1758:

"At No. 6 in Trinity St. near the College Green. On Monday

after Easter will be opened a School for

young Ladies, by Mary More and Sisters, where will be carefully

taught French, Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, and Needlework. Young Ladies

boarded on reasonable terms."

A few weeks later an additional line appears: "A dancing master will properly

attend."

At this time Hannah More was only thirteen, so that the statements as to her

having been a chief promoter of the school are altogether incorrect and

absurd. Mary More, then barely twenty-one, seems to have been

one of those thoroughly unselfish women of whom there are but too few; and

she delighted in developing the taste for languages and literature which her

more gifted younger sister very early evinced. The school prospered from the

first,—and no wonder, for the mistresses were no ordinary women; and

from their wise teaching scores of girls went out, strengthened in principle

as well as richer in knowledge, into a world where "it was the fashion to be

irreligious."

Hannah took

her share in the school duties when she was old enough to do so; but at

twenty-two years of age a wealthy but elderly admirer appeared upon the

scene, and her engagement, to Mr Turner of Wraxall, was

doubtless a source of much satisfaction to the little circle, who in

1762 had moved to a large house in Park Street.The street still remains, and the house is now known as

"Hannah More Hall.". . . For six

years the curious courtship continued; but at the last moment the gentleman

decided that he did not feel equal to the responsibilities of matrimony,

and, after compensating his Amaryllis for her "blighted hopes" with an

annuity variously computed at £200 and £400 per annum, he died a

bachelor.

To the last this quaint pair entertained a "cordial respect" for each other,

and by his will she found herself the possessor of a legacy of £1000.

The

annuity enabled her to feel independent and to devote herself to the study

of literature, for which she was really far more suited than to the

consideration of the "varying moods" of a middle-aged landowner. The literary world is

distinctly the richer, so that we are able honestly to rejoice at the

capricious conduct of the vacillating lover.

Her first

work, The Search after Happiness,

published in 1773, was an immediate success, and at once

secured her a footing among the distinguished writers of that day.

At twenty-eight the obscure schoolmaster's

daughter awoke to find herself famous. It was a far cry from Bristol to London in those days. George Stephenson was

still unborn, and the natural terrors of the journey were increased by the

hordes of highwaymen with which the roads were infested. It is a

red-letter day when, in 1773, Hannah More starts on her first

pilgrimage to London. Every step of the way is fraught with interest to

the young traveller, whose ideal, Samuel Johnson, looms in elephantine

grandeur as at the farther side of a great gulf. She has heard of him, read

of him, dreamed of him, and now she is to see her hero—the scarred, uncouth

scholar whose brilliant intellect could make even his enemies admire and

tremble and who has had the solitary glory of creating a faithful

biographer.

Arrived in London, she is the cynosure

of all eyes; and as if to prove that Barabbas was not a

publisher, T. Cadell of the Strand made her the handsome offer of

the same remuneration for Sir Eldred of the

Bower and the Bleeding

Well as Goldsmith had received for the

Deserted Village—"be it what

it might." This now "unconsidered trifle" was then much praised—and, what is

still more remarkable, and certainly not in the very least a matter of

sequence, it was also much read.

The following are Green-Armytage’s personal assessments, in 1908,

of Augustine Birrell’s criticism of Hannah More in

Birrell’s Collected Essays: Res Judicatae

(1892).

Hannah More among the prophets and Hannah More as a

humorist are, possibly, characterisations under which she has not appeared

upon any stage within the last fifty years. But this is a generation

that knows not Hannah! and certainly, whoever else knows anything about her,

Mr Augustine Birrell does not. He may have read her Life and Works from cover to cover, but a man only

gets out of a book that which he himself is capable of assimilating, and Mr

Birrell is evidently not en rapport with his subject, and had better have

left his unworthy Essay unwritten. . .

It has a spurious smartness about it which makes its

misstatements all the more distasteful to an earnest student of her time,

especially when coupled with a condescending air of patronage and

superiority which sits ill upon a man who has not done, and could not do,

one tithe of the work that was done by this delicate woman. . .

As Charles Lamb whimsically said, "She is not Hany

More," and Mr Birrell can therefore criticize as harshly as he

thinks fit; but with men like Johnson, Garrick,

Pitt, Wesley, and Macaulay as

counsel for the defence, even her greatest admirers of to-day can afford to

smile. In his self-evident desire to be smart, he has forgotten alike the

"scrupulous

justice which belongs to critics and the delicacy towards the sex which

belongs to gentlemen," with which the British

Review wrote of her in 1811. To speak of an old woman

and a dead woman as a "huge conger-eel floundering in a sea of

dingy morality" may be smart writing, but its taste is

questionable, to say the least. The careless condescension with which, in

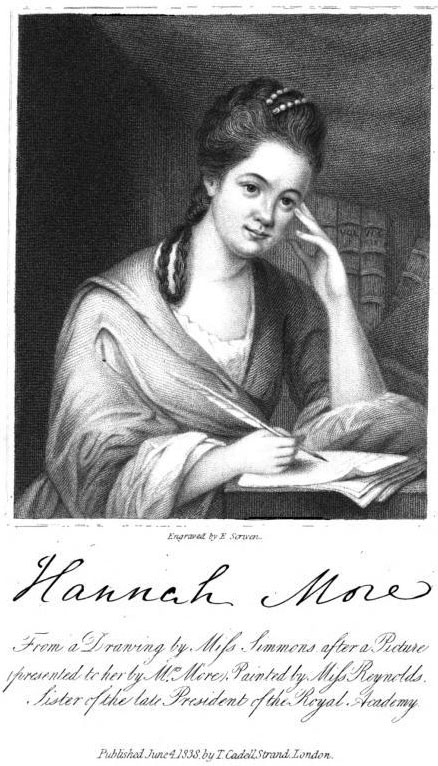

later years, he acknowledges her lineaments to be "very pleasant" is almost

comical, when one looks at the strong sweet

old face with its halo of silver curls, to which Time has but added the

beautiful serenity of a well-spent life.

The Bristol

election of 1774 was very hotly contested, and the intelligent

and tactful sisters did their utmost to secure the return of the Whig

candidates, Cruger and Burke, who were

triumphantly declared successful by a large majority. This election, "the

most interesting that ever took place in Bristol," must have been a time of unwonted excitement for the

quiet sisterhood. . . . From 1775 her time was largely spent in

the very heart of Londonlife, and amid

all the social and intellectual gaieties which the best society afforded.

Her account of the trial of Elizabeth, Countess of Bristol, is

full of humour, and her letters are brimming with vivacity and observant

shrewdness, verifying her own declaration in her seventy-first year, "My temper is

naturally gay. This gayety even time and sickness have not much

impaired. I have carried too much sail. Nothing but the grace of God and

frequent attacks of very severe sickness could have kept me in tolerable

order. If I am no better with all these visitations, what should I have

been without them?"

Her tragedy, Percy, was produced at

Covent Garden Theatre in 1777. Four thousand copies of the

"book o' the words" were sold in a fortnight, and the play itself had an

unusually long run, David Garrick taking the principal

character, and enriching the performance by a prologue and epilogue of his

own. This

tragedy seems to have made the greatest success of any of her plays, and

excited the emotions alike of rich and poor. Johnson,

Garrick, and Pitt united in praising it, and

the author's place in the literary world was definitely secured.

For several years she lived a life of adulation, but throughout it all she

held tight on to her Sundays, and maintained a degree of real simpleness

which could only be regarded as remarkable, were not her early influences

taken into account. The

Jesuits have a saying, "Give us a child to train until he be nine years

old, and you may do what you like with him afterwards," and of the truth

of this Hannah More is an example.

The

purity of her life remained untouched, and if to our modern notions she

sometimes appears almost "priggish," it must be remembered that the line

between faith and unfaith was more sharply defined in her day than it is

now, and she was bold to avow that "Propriety is to a woman what the

great Roman critic said that action is to an orator,—it is the first,

the second, and the third requisite."

Her Utopian schemes of reforming the

character of theatrical representations seems to have died with Garrick, and

the sight of his coffin in the same room where she had but lately witnessed

him performing as Macbeth, made her resolve definitely to devote her talents

to higher uses. Garrick was buried in 1779, amid

great mourning and splendid pomp, in the great Abbey of Westminster, but on the very night of his

funeral the play-houses were as crowded as if no such thing had occurred,

and the mourners of the day shared in all the revelries of the night. Such a

satire upon "the fashion of this world" helped no doubt to intensify the

sadness of his sudden death, and from that time the brilliant life of

London, with all its triumphs and successes, seems to have palled upon her.

With a

woman of her nature this was no mere "phase," resulting from the painful

emotions of the time, but a gradual deepening of an innate piety, for which

thousands have had reason to be thankful.Never again did she enter a

theatre, even when Sarah Siddons was taking a prominent part in

Percy, and we cannot but admire the consistent

striving after the "highest," which is the keynote of all her subsequent

career.

In 1785 we see her installed as mistress of a tiny house called

"Cowslip Green," about ten miles

from Cheddar; and when in

1789 her sisters gave up the Park Street school and settled in Pulteney Street, Bath, she spent part of every winter with them, and part with

Mrs Garrick, for whom she retained the greatest affection and

respect. John Wesley much deprecated her retirement to the

country, and sent her a message more emphatic than grammatical, which runs

thus—

"Tell her,"

said he, "to live in the world. There is her sphere of usefulness. They

will not let us come near them."

But retreat did not mean idleness, and, from the quiet village of Wrington, year by year issued

pamphlets and tracts, which circulated in millions, and were instrumental in

counteracting the torrent of infidel and licentious literature which

threatened to inundate and undermine England—her religion and her government. Realising the enormous

influence wielded by those in the van of society, she published an anonymous

pamphlet on The Religion of the Fashionable

World, and, in spite of the absence of "original

thought and happy phrases" which Mr Birrell deplores,

its authorship was speedily discovered by Dr Porteous, Bishop

of London, who at once declared "Aut Morus, aut angelus!" Her Village Politics was published by

Rivington instead of by Cadell, and under the

pseudonym “Will Chip,” in order to divert

suspicion from its writer, and, to her amusement and gratification, it was

sent to her by every post with laudatory reviews recommending its

propagation in her own neighbourhood. It sold by the thousands....

It was in 1789

that William Wilberforce visited the sisters at Cowslip Green, and during his visit an

immense impulse was given to their work among the poor of the neighbourhood.

After visiting the magnificent gorge known as "Cheddar Cliffs" he was

observed to be unusually silent, but in the evening he exclaimed, a propos of the amazing ignorance of the people

there, "Miss Hannah,

something must be done—if you will be at the

trouble, I will be at the expense."

This was

practically another turning-point in the life of Miss Hannah More; and her

familiarity with the cottagers, her own tireless energy and abounding

sympathy, enabled her to write as powerfully of "Tom White the Postilion"

and "Black Giles the Poacher," as she had written before in Hints to a Princess and The

Manners of the Great.

But the schemes of Wilberforce and the More sisters for benefiting the

population met with no response from the people of that benighted region.

The very poor lived in a world of their own—less than half-civilised; and

even among the farmers, the only argument for the better education of the

children that had any effect was that "while they were at Sunday-school they

could not be robbing orchards." But these women

worked on undauntedly—through evil and good report—with the energy of the

Old and the sweetness of the New Dispensation, until schools and scholars

were alike established, and out of a seeming Chaos order and discipline were

evolved.

"Something must be

done," Wilberforce had said, and "Miss Hannah" did it. She aimed at

the highest, but protested most strongly against making the poor into

philosophers. Her desire to keep them

in their proper place is now out of fashion, and the School Boards of

1906 would scoff at the short and simple lessons of

1799.

Her

theory was, "suitable education for each and

Christian education for all," and the wedding-present for a girl who was

married from Hannah More's

schools was "a pair of white stockings knitted by herself, five

shillings, and a Bible."

In 1802 the house now known as Barley Wood was finished, and thither the five sisters repaired,

living happily together as they had done in the old days, to the admiring

surprise of Dr Johnson, whose acquaintance she had so coveted

nearly thirty years before. To Barley

Wood often resorted many leaders of the "Clapham Sect." Henry

Thornton, Zachary Macaulay,

Wilberforce, and others were gladly welcomed to its

old-fashioned hospitalities by the five ladies, now no longer young, who had

permanently fixed their abode within its walls.

Thence issued the series of "Cheap Repository Tracts" published by the

S.P.C.K., which had an enormous circulation, and which show that

"Patty" also had a sprightly fancy and a ready pen. This sister

we may fairly suppose to have been the most akin to "Miss Hannah," as hers

is the name which occurs most frequently in connection with the social and

literary interests of the latter; but all the five, in their devotion to one

another, are perhaps unique in domestic annals. Of these tracts the most

popular was The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain, the

hero of which was modelled on a man whom she herself had met. The extraordinary

sale of 1,000,000 copies shows its admirable suitability to, and popularity

with, the class for whom it, as well as the other tracts, was written.

The atmosphere of Barley Wood was often enlivened by visits from

Zachary Macaulay's son, little Thomas

Babington, afterwards Lord Macaulay. . . It was Hannah More who

first started Lord Macaulay's library, writing to advise him, when only six

years old, to "lay a

little tiny corner-stone" for the same. She was said to have had

the rare gift of knowing how to live with both young and old, and she often

kept Macaulay with her for weeks together, the youthful prodigy meanwhile

declaiming poetry and reading prose by the hour. His subsequent appreciation

of moral goodness and his persevering energy in acquiring knowledge may be

fairly traced to the influences of his childhood; but his "negativism" on

religious subjects is a matter of surprise and regret, and his old friend of

Barley Wood so deeply felt his defection "from the party of the saints to the party of the

Whigs," as Mr Maurice significantly says, that she

changed her intention of leaving him her own valuable library, as a

testimony of her disapproval.

With little

outward eventfulness flowed on those next few years, save for the inevitable

visits of death, until in 1819 the last blow was struck in the

passing away of Patty, whose loving co-operation and care had cheered every

step of her career from the time when the little sisters had sung themselves

to sleep in the nursery bed at Stapleton…

Unfitted by ill-health, temperament, and having to cope with the

deceitfulness of servants, she determined to move into Clifton, and in a smaller house, with a fresh staff of

servants, to begin another chapter of her life—at eighty-three years of age.

Three days a-week, from twelve to three o'clock, were set apart for the

reception of visitors, and when remonstrated with for thus fatiguing

herself, the unselfish old lady had always four reasons ready, which she

considered unanswerable—If old, she saw them "out of respect; if

young, hoping to do them good; if from a distance, because they had come

from far; if from near home, because neighbours would be naturally

aggrieved at being excluded when she was open to receiving

strangers."

As

her strength for earthly journeyings declined, her thoughts centred more and

more on the "land of far distances," and she

realised fully that the time of her departure was at hand. Her final illness

lasted for eleven months—long enough for a whole treasury of dying sayings;

but the "gayety" of which she spoke in her seventy-first year never forsook

her, and is not one of the least charming traits in the character of this

quiet reformer.

On the

7th of September the end came, and after lying in a

semi-delirious state for many hours, she passed away, murmuring as her last

conscious words, "Patty—joy."

There is a deep pathos in the association of the words. One could almost

believe that a glimpse of that beloved sister who had shared in so much of

her earthly happiness was vouchsafed to her, waiting perhaps to welcome her

within the golden gates of that beautiful country wherein is "fulness of joy, and

pleasures for evermore."

On the

13th of September 1833, every church in Bristol rang a muffled peal, and the

tired body of Hannah More was laid to rest in Wrington churchyard, amid every

manifestation of respectful mourning. There lie the five More sisters, of

whom Johnson had said, "I love you all!"…

Judged by the

present pyrotechnic style of literary composition, the success of her work

seems phenomenal; but in her day books were not so much a matter of daily

outputting as now, and for a publisher to be delivered into the hands of a

woman was a welcome novelty. Phrases, too, which to us seem "stilted" almost

to absurdity, were then only the courtesies of everyday life—so much is the

standard of politeness in its decadence. But it is not

too much to say that Hannah More will always be remembered with respectful

admiration, even by men of more literary culture than William

Wilberforce, who said that he would "rather appear in

Heaven as the author of The Shepherd of Salisbury

Plain than as the author of Peveril of the

Peak."

Such

men as the shepherd doubtless still exist, though their conditions may be

different; and among the many new editions that are continually cropping up,

perhaps "Coelebs" and "Will Chip" may yet appear with their wholesome

influences, to the displacement of some of our modern writers and the

benefit of the next generation.

Her large-heartedness is conspicuously evidenced in her life-long friendship

with Mrs Garrick—née Eva Veigel—"La Violetta" of the Viennese ballet.

The fact of

a staunch Evangelical and a loyal Romanist being able to spend twenty

winters together on terms of closest intimacy speaks for itself, though it

is quite likely that in these days when the Italian Mission is becoming more

and more realised as a proselytising agency, such an unfettered intercourse

would be almost impossible, or at any rate impracticable. Hannah More says

candidly, "We dispute

like a couple of Jesuits"; but it is clear that the love on either

side was in no way affected, nor the possibility of compromise

entertained.

Of More's character as exhibited by her handwriting,

Green-Armytage concludes: The versatility which shows itself in

Hannah More's handwriting is manifested by the readiness with which she

devoted the ambitions, which had been fostered under Garrick's

guidance, to other interests; and what dramatic powers she possessed were

quickly overshadowed by the characteristic enthusiasm with which she threw

herself into religious and philanthropic reforms. This divine enthusiasm, however,

never waned, as her last book on The Spirit of

Prayer clearly shows. It proclaims, in tones as

distinct, though less forcible, Carlyle's solemn message to the

world—"No

prayer, no religion, or at least only a dumb and lamed one! Prayer is

and remains always a native and deepest impulse of the soul of man; and,

correctly gone about, is of the very highest benefit (nay, one might say

indispensability) to every man aiming morally high in this world. Prayer

is a turning of one's soul in heroic reverence, in infinite desire and

endeavour, towards the Highest, the All Excellent, Omnipotent,

Supreme."

"Hannah More is

incapable of a literary resurrection," says the Minister of

Education.... It may be so, but when the struggle of 1906

is only remembered as one more illustration of the extraordinary bias which

early training can give to the mind of a man learned in the Law and the

Scriptures, the Church shall be quietly extending her boundaries throughout

the world, and educating generations of children whose Imperial instincts

shall march side by side with the principles and practices for which Hannah

More pleaded more than a hundred years ago.

Practical Piety is going

out of fashion quite fast enough: we do not want to ignore its Principles

also.

Who knows but that the

"ever- rolling

waves" of Time may once again bear upon their crests the quaint

old text-books of God-fearing Faith and Morality which were written—and

acted upon—by the little lady of Barley

Wood!

A. J. Green-Armytage’s

biography of Hannah More takes a sympathetic and admiring view of More’s

religiosity and literary merits, while at the same time keeping with a

largely traditional view of the role of the independent woman.

Additionally, Green-Armytage appears to have a personal quarrel with the

criticism leveled by Augustine Birrell on Hannah More’s

writing; Green-Armytage regards More as having a much higher degree of

literary talent than does Birrell.