DOROTHY WYNDLOW PATTISON was born at Hauxwell, near Richmond, Yorkshire, England, on January 16th,

1832, the eleventh of twelve children (the tenth daughter) of the

Rev. Mark James Pattison

(1788-1865) and Jane Winn

(1793-1860), daughter of a banker and former mayor of

Richmond. Rev. Pattison was strictly evangelical and mentally unstable; his

wife was induced to commit him to an asylum for almost a year in

1834-1835. The eldest son, Mark Pattison

(1813-1884), became an Oxford don and for a time joined the

high-church Oxford Movement. The father tried to cut off all communication

between the nine sisters at home and this supposed Papist infection, though

Mark fostered Dorothy's education and she was often his companion on holidays and visits.

The

tension between father and son set the stage for Dorothy's non-dogmatic

religious fervor, but in her career she broke away from both father and

brother.

DOROTHY WYNDLOW PATTISON was born at Hauxwell, near Richmond, Yorkshire, England, on January 16th,

1832, the eleventh of twelve children (the tenth daughter) of the

Rev. Mark James Pattison

(1788-1865) and Jane Winn

(1793-1860), daughter of a banker and former mayor of

Richmond. Rev. Pattison was strictly evangelical and mentally unstable; his

wife was induced to commit him to an asylum for almost a year in

1834-1835. The eldest son, Mark Pattison

(1813-1884), became an Oxford don and for a time joined the

high-church Oxford Movement. The father tried to cut off all communication

between the nine sisters at home and this supposed Papist infection, though

Mark fostered Dorothy's education and she was often his companion on holidays and visits.

The

tension between father and son set the stage for Dorothy's non-dogmatic

religious fervor, but in her career she broke away from both father and

brother.

Many biographies depict a happy childhood for the somewhat frail but

beautiful child whom her father's called his "Little Sunshine."

Dorothy is

said to have "inherited from her father, who was of a Devonshire family,

that finely proportioned and graceful figure... and from her mother...those

lovely features which drew forth the admiration of everyone who had the

pleasure of knowing her" (M + S, 241). The sisters were occupied in caring

for their ailing mother, works of charity among the villagers, and outdoor

exercise, including Dorothy's great pleasure, riding to hounds. Yet the

father gave formal education to his two sons only, resisted all suitors and

disowned the daughters who married, and tried in every way to contain his

daughters and wife within the home and according to his will. Biographies of

Dorothy emphasize her innate strong will, source of the greatness as well as

the difficulties of her life.

Although Dorothy wished to join Florence

Nightingale as a nurse during the Crimean War (1853-1856), her father forbade

her to leave home, pointing out that without training, she would be "worse

than useless" on the front.

Most biographies omit what the ODNB matter-of-factly understates: "Tall and

pretty, Dorothy Pattison was in love with several men during her life, both before and after

she took religious vows."

An engagement to a handsome farmer

and soon another to a respectable clergymen both came to nothing,

under the disapproval of her family and her own reluctance to give up her

vocation for anything less than passion.

After Dorothy's mother

died

in 1861,

Dorothy won the great point of independence, serving as village

schoolmistress at Little Woolston,

Buckinghamshire, for three years. There, "She had to live alone in a

cottage, and do everything for her self; but the people never for a moment

doubted she was a real lady, and always treated her with great respect" (M +

S 242).

One of her frequent illnesses led her to take a holiday to

recuperate at Coatham, near

Middlesborough, where she visited an Anglican sisterhood and observed their

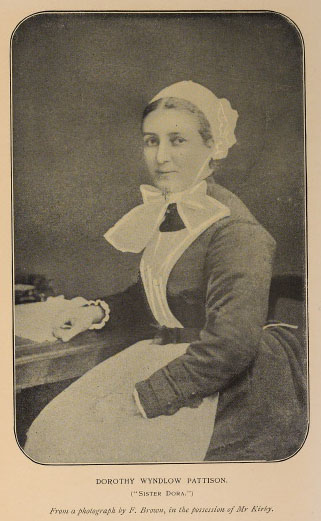

work in a convalescent home. In September 1864 she joined the Christ Church sisterhood, adopting

the name Sister Dora. Most accounts stress her humiliation under the

housework and impersonal discipline, though she has already prided herself

on being able to cook.

Many accounts

tell of her bursting into tears "when the beds which she had just put in

order were all pulled to pieces by some superior authority, who did not

approve of the method in which they were made" (M + S 242).

The sisterhood trained and then dispatched nurses to small hospitals and

private patients, and for some years Sister Dora's assignments frequently

changed. In January 1865 she was sent to Walsall, a manufacturing district near Birmingham, where a small cottage hospital had been

formed in 1863 for emergency treatment of industrial injuries from the coal

mines, iron pits, tanneries, and railways. Her decision to join the

sisterhood meant a breach with her family, who considered the work

demeaning; Mark disapproved of her "romance" with self-sacrifice. Many

biographies repeat the idea that the sisterhood prevented her from attending

her father's deathbed and funeral (1865), and that this led to her decision

to leave the sisterhood. More recent accounts make it clear that the breach

with the sisterhood came later, when she made her own decisions about her

nursing assignments, and that bad relations with her family as well as

mistimed messages led to her not going home at that time.

The first appearance of volunteer nurses, resembling Catholic nuns, caused

some distrust. and there are anecdotes about local people

believing that secret rituals were performed in a closed-off room in the

hospital. In one anecdote, a boy

threw a stone that hit Sister Dora on the forehead, calling her a "Sister of

Misery." But soon professional men and workers all were won over by Sister

Dora's beauty, humor, graceful manners, and dedicated hard work. By 1867, when a new hospital had

to be built, Sister Dora was put in charge, and clearly demonstrated her

administrative skills as well as her increasing expertise in treating wounds

and illnesses. Religion infused everything she did, from prayers and songs

to the stories she told and letters she wrote explaining her vocation, but

evidently it was a non-sectarian, populist form of belief that attracted her

patients and helped them to recover. She often said when a patient's bell

would wake her in the night, "The Master is come, and calleth for thee!"

She once wrote to a friend, who was engaging a servant for the hospital, "this

is not an ordinary house, or even a hospital...all who serve

here...ought to have one rule, love for God, and

then, I need not say, love for their work."

All biographies of Sister Dora assemble the picture of an admirable

personality, some pushing the limits of credibility toward the heights of

sainthood. At the same time, almost all note the flaw that she herself

acknowledged, self-will. But without her driving sense of purpose and

resistance to obstacles, "it is doubtful whether she could have achieved all

she did," as Mabie and Stephen put it (following Lonsdale and Baring-Gould).

Women who came to Walsall to

study nursing with her (she often had "lady-pupils") objected that

she would not let anyone help her and did not delegate well, even that she

had little appreciation of women. From a later perspective, Sister Dora

seems to have gained power through a version of self-denial not dissimilar

to an eating disorder or suicidal tendencies; the famous risks she took with

infections make more sense as ways to court death when her own desires were

defeated.

As noted, the biographies downplay Sister Dora's series of attachments to

suitors; most seem unaware of any such possibilities of marriage, though

some note that she was severely tested by her love for a medical man, possibly Redfern Davies, whom she met in

Walsall, her equal in many qualities but an unbeliever. After a struggle,

she decided to continue her vocation and sustain her dedication to Jesus.

Only since the 1930s have letters reappeared that reveal that Sister Dora

had a relationship in 1876 with a younger man, an industrialist, Kenyon Jones. Jo Manton considers

Sister Dora "the prisoner of her own legend" (306); she had to keep their

love a secret. The legend drew upon the beauty, purity, and gentility of a

lady, but her vocation permitted considerable bodily intimacy and

participation in graphic scenes and physical tasks unusual for the type.

There are several episodes of her

intimacy with dying or wounded men that combine sympathy, horror, and iconic

heroism. One night she came

to the home of a man who was dying of small-pox; all his relatives and

neighbors had fled, including a woman she had sent to buy a candle, who

never returned. As she sat with the man, he asked her, "Sister, kiss me

before I die." And as the candle expired, she embraced the man, with his

running sores, and sat with him in the darkness all night, finding in

the morning that he had died in her arms.

Another favorite narrative

tells of a boy whose right arm had been crushed by machinery. The

surgeon insisted that it must be amputated to save the boy's life, but

Sister Dora wished to try to save the limb that meant the boy's

livelihood. The surgeon warned her (some accounts consider him offended

by her challenge to his authority) that the life of the patient was her

responsibility. With three weeks' constant care and prayer to heal the

wound, the arm became whole and healthy, and we are told the surgeon was

impressed, as the boy was forever grateful. He is said to have gained

the nickname "Sister's Arm." There are less common but equally uplifting

episodes of her counselling a young dying girl or befriending a

convalescent child who never forgot her care; children figure more

generally as testimony to Sister Dora's nurturing love. Walsall was full

of former patients and family members who remembered her generous,

personal care and who would come to see how she was during any illness.

Every Sunday "Sister's Arm" would walk many miles to the hospital to ask

for Sister Dora, and say "Tell her it's her arm

that rang the bell" (Fawcett 190-91)

Sister

Dora worked with little pause throughout the day and night, visiting all

beds, supervising all meals, often skipping her own food or rest. She was

seldom seen sitting down. This work was enlivened with a sense of

performance and playfulness, singing and telling tales that entertained her

patients, whom she gave nicknames and special notice or favors. Yet the work

was repeatedly interrupted by serious illness; she seemed careless about

infection, coming in contact with all kinds of disease and exposed to all

weathers.

Other than her illnesses, her years of service in Walsall are shaped by

memorable catastrophes for the workers in the town, events featured in the

vividly realist bas-reliefs surrounding the base of the statue that Walsall

erected after her death. One

was colliery disaster in 1872, and another was an explosion in 1875 of a

furnace at Birchett's Iron Works which covered eleven men in molten

metal.

For ten days

without resting Sister Dora bravely tended to the victims in a special ward

that pupil-nurses and doctors were loath to enter, faced with the stench,

the cries, and the sight of charred bodies. Only two men survived. Yet another heroic episode

came with a renewed epidemic of small-pox; to convince the people to go

to a quarantine hospital, Sister Dora volunteered to place herself in

isolation there. She showed no concern for her own risk, but it meant

many months of hard labor because there were only a few unreliable

servants.

Contemporary newspapers before and after her death began to record the

remarkable deeds of this self-sacrificing servant of the suffering poor. Her

medical colleagues attested to her skill in various branches of care, from

surgery to the dressing of wounds to the treatment of eye injuries; late in

life she studied the work of Lister on antiseptic treatment in London, but

she had chosen not to pursue further medical training in favor of her

particular hands-on mission among the workers. This mission included

rounding up prostitutes and clearing out the pubs for midnight prayer meetings in the

town. Many locals recalled her with reverence as a kind of saint, and some

believed she could work miracles. Gifts and testimonials included a pony and

cart given to her by railway men; she used it to make house calls, and to

take convalescents on jaunts. She particularly liked to use her own funds to

sponsor feasts for patients and holidays for the poor children who were

recovering from illness or injury. She hid the records of the extent of her

charities.

For many months she also kept secret her mortal illness, an

inoperable breast cancer, continuing to work as long as she could and

planning the construction and move into a new hospital that was begun in

1877. Here, a passage in Baring-Gould and Mabie and Stephen offers a

portrait of the heroine's motives:

She could not endure pity. She, to whom everybody had learnt

instinctively to turn for help and consolation, on whom others leant for

support, must she now come down to ask of them sympathy and comfort? The

pride of life was still surging up in her, that pride which had made her

glory in her physical strength for its own sake, as well as for its manifold

uses in the service of her Master. True, she had been long living two lives

inseparably blended: the outward life of hard, unceasing toil; the inner, a

constant communion with the unseen world, the existence of which she

realised to an extent which not even those who saw the most of her could

appreciate. To all the poor, ignorant beings whose souls she tried to reach

by means of their maimed bodies, she was, indeed, the personification of all

that they could conceive as lovable, holy and merciful in the Saviour. (M+S

259)

After a brief holiday, she returned to Walsall in her final illness, and died on 24 December, 1878. Her

last wish, they say, was to die alone. And some said, and had to be convinced

otherwise, that she converted to Catholicism on her deathbed.

Her funeral

on the 28th of December was a town spectacle, a procession of thousands. In

1886, a statue by Francis Williamson was erected in another public ceremony,

following upon a stained-glass window in St. Matthew's Church (1882-1883).

The Walsall writer of "A Review," quoted by Baring-Gould and Mabie and

Stephens, concludes:

She

is no idol to us, but we worship her memory as the most saintly thing

that was ever given us. Her name is immortalised, both by her own

surpassing goodness, and by the love of a whole people for her—a love

that will survive through generations, and give a magic and a music to

those simple words, "Sister Dora," long after we shall have passed away.

There was little we could ever do—there was nothing she would let us

do—to relieve the self-imposed rigours of her life; but we love her in

all sincerity, and now in our helplessness we find a serene joy in the

knowledge that to her, as surely as to any human soul, will be spoken

the divine words: "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these

my brethren, ye have done it unto Me."(M + S 264)

Sister Dora's reputation as a modern saint was international for some

decades. She appeared in as many as twenty collective biographies besides

numerous biographical reference works and countless essays and articles. And

even Susan McGann's 2004 biography in ODNB ends with this same quotation

from Matthew 25:40.